The Social Architecture of Impactful Communities

A guide for community builders creating impactful organizations.

In Bowling Alone, author Robert Putnam chronicles America’s declining participation in membership organizations of all kinds, including churches, labor unions, rotary clubs, and volunteer groups.

This disengagement has coincided with increasing feelings of isolation. In 1985 Americans reported having an average of 2.94 close friends. By 2004 this number fell to 2.08. In the same period, the number of Americans who reported having no close friends outside the family jumped from 36% to 53%. While we don't yet know the impact of quarantine on these measures, it's hard to imagine that sheltering in place is leading to improvements.

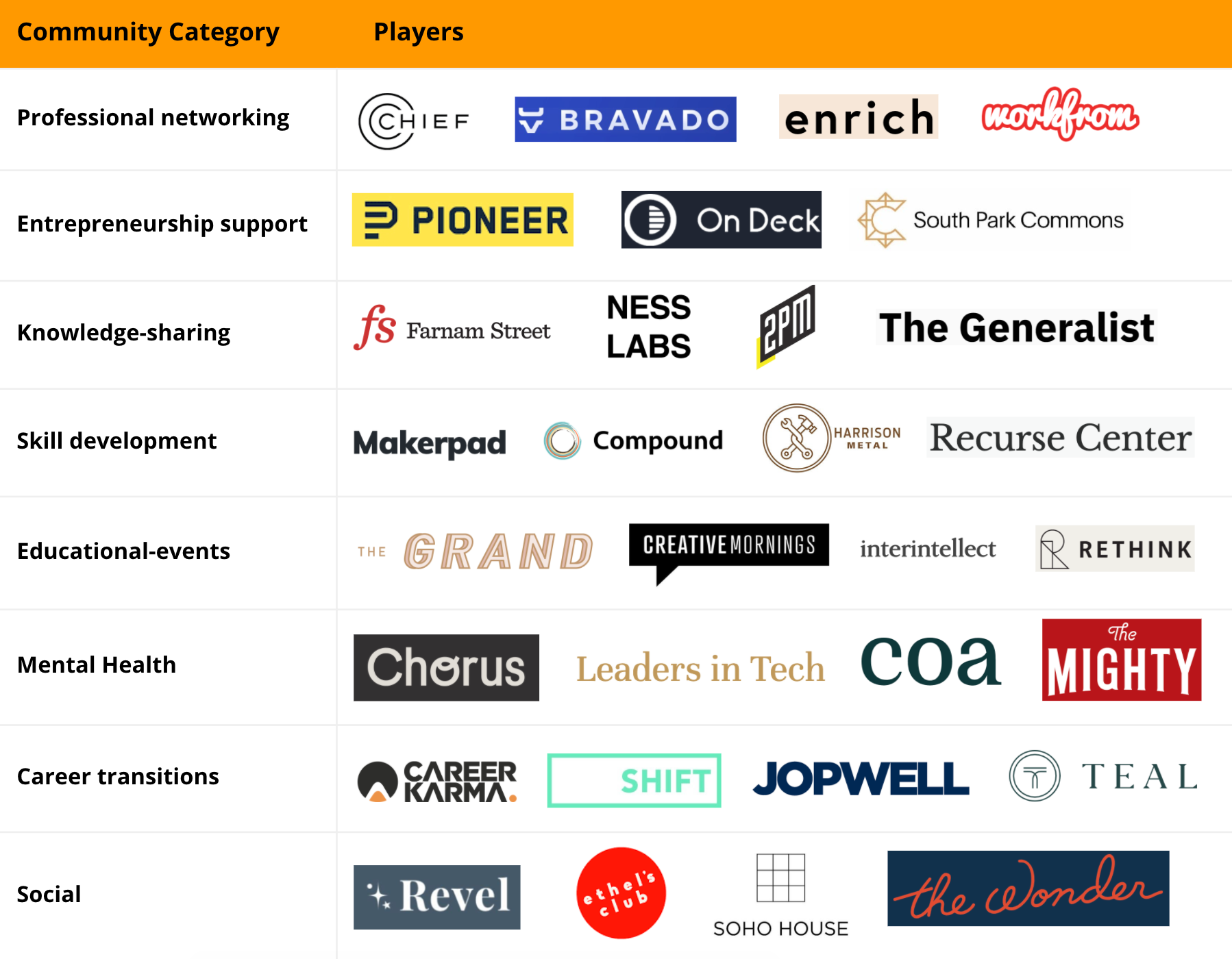

In recent years, a crop of new communities has sprung up across multiple categories that may have a shot at restoring some of America’s diminished social capital. For example:

While some of these organizations may have started with purely financial motivations, I suspect that most of their founders aspire to build communities that can replace some of the social capital that America’s waning institutions once provided.

They will, of course, have big shoes to fill. To replace the bonds that institutions like churches and labor unions once provided, our community architects will need to understand and deploy the social dynamics that have driven impactful communities for centuries.

During my time building, managing, and participating in a spectrum of thriving communities, I've learned how impactful groups are structured. In this guide, I’ll synthesize what I’ve learned into advice that you can apply to your own community and make a profound impact on the lives of your members.

Why do people join communities?

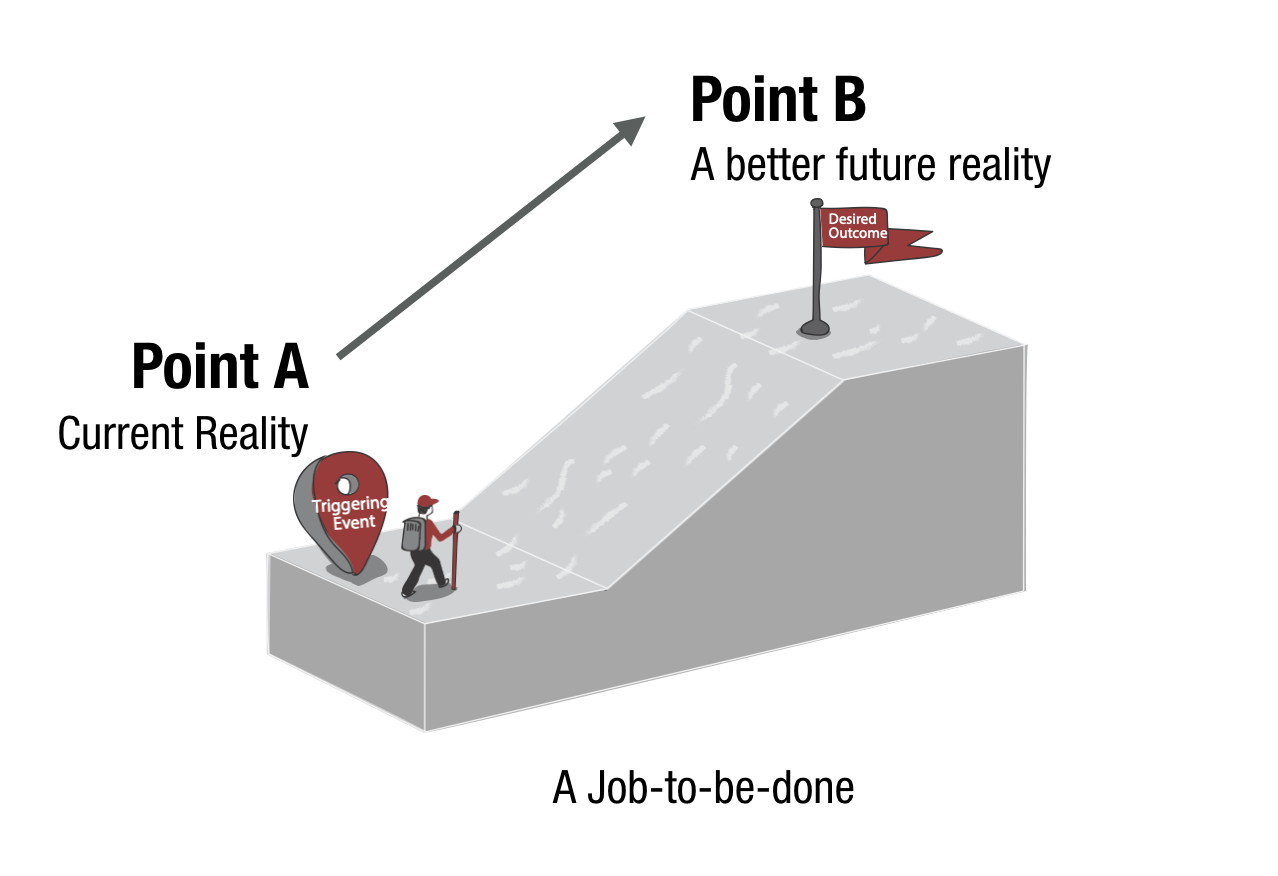

In The Innovator’s Solution, professor Clay Christensen introduced the Jobs-to-be-done theory to explain how consumers “hire” solutions to improve their lives. The theory posits that people look for the right solution to help them get from their current state to a more desirable one (smarter, loved, happier, healthier, etc.).

Individuals typically “hire” communities to accomplish transitions that require human connection. A startup founder who wants to become a better leader applies to Leaders in Tech to get the type of honest feedback needed for professional growth. The parent of a child with a rare disease might join The Mighty to get caretaking advice from parents in similar situations.

Impactful communities have environments that make it easy for members to connect and create value for one another. Sometimes the connections themselves create most of the value. In other situations, the value comes from what gets exchanged (expertise, status, motivation, etc.) after members connect. Either way, it takes a thoughtfully designed community for these interactions to take place.

Building these types of environments isn’t easy. Unlike an app, your members can’t be programmed to consistently deliver valuable experiences for one another. That’s why it’s critical to thoughtfully design your community’s social architecture to maximize the value that gets exchanged between members.

Member quality determines community success

To visualize what makes a community successful, it can help to build a flywheel diagram to show which inputs produce positive outputs. The flywheel for a well-functioning community might look something like this:

New Member demand helps the community to grow in size generating more membership dues that community leaders can invest in capabilities like events, tools, and staff. These capabilities increase and improve interactions between members, making them more likely to create value for one another and renew their memberships. A healthy member base enhances the community’s reputation, which spurs more new member demand.

However, as anyone who’s been part of a community knows, bigger communities don’t always have better member experiences. Poorly chosen members can have significant negative impacts on a community.

Poorly-chosen members can:

- Make it harder for communities to invest in capabilities like events or forums, since these members are likely to abuse them.

- Decrease the quality of member interactions as well as the quantity (since good members may end up avoiding the group)

- Reduce member value by ruining group cohesion and reducing the ability of members to signal high status through their affiliation with the group

- Lower member retention since they diminish the value members get from the group

- Diminish the community’s reputation since it’s clear the group does not have a strong filter for who they admit

- Suppress new member demand since the community will drive less positive referrals

Well-chosen members, on the other hand, can have the opposite effect on each of these variables.

Context matters. While a junior UX designer might add a lot of value to a group of job seekers trying to break into the field, he likely has little to offer to a group of high-level design leaders. To determine who’s a fit, you’ll want to get an understanding of your ideal member profile and make sure the applicants you are admitting are capable of creating value for your chosen persona.

When evaluating applicants, it can help try to place them into one of the following categories:

- Adders will hopefully be the core of your group. They do their best to create more value than they capture and generally make the community a better place.

- Subtractors are those who are simply not good fits for your group because they can’t provide the type of value that other members want. If one gets through your filter, it’s not the end of the world, but you will risk damaging your member experience if this becomes a pattern.

- Dividers can be toxic to the point that they end up negatively impacting other members’ behavior in their orbit, creating fights, and sometimes even staging coups against group leaders. If their behavior goes unchecked, they can cause no end of trouble. If you identify one of these people in your group, get them out.

- Multipliers are members whose positive behavior elevates everyone they come in contact with. These people are quite rare, but when you find one in your community, do anything you can to keep them.

You’ll also want to consider whether each member can make a distinctive contribution to the rest of the group, or if they just bring more of the same. Amazon wouldn’t be a useful place to shop if it didn’t have a variety of products. Similarly, a community can’t provide much value if its members are too similar. You want to have a good assortment of people with different attitudes, skill sets, and life experiences, so your members can find better matches with one another. Prioritizing group diversity also ensures that members can find their niche and don’t feel too competitive with one another.

Pro Tip: Marquee Members

Marquee members are individuals who get recruited into the group based on their external prestige. Early on, you might be tempted to recruit one or two members like this to draw others into the group. However, this is a risky strategy. New members will naturally look to people with external status to determine how to behave. If your group doesn’t yet have its value delivery system figured out, you risk your marquee members disengaging from the group and spreading their attitude to others.

Be careful over-investing in community capabilities

While members can create a good deal of value, they won’t invest time and energy into the community if they feel like they are doing all the work. That’s why as your member base grows, it’s worth investing in capabilities to help your members discover and interact with one another like:

- Event hosting to throw retreats, webinars, happy hours, etc.

- Content production to publicize the accomplishments of members

- Member directories to enable member discovery

- Knowledge repositories to artifact and disseminate shared expertise

- Forum hosting to create spaces for questions to get asked and answered

- Chat moderation to promote quality interactions

Most community leaders make the mistake of assuming capabilities like these provide the bulk of benefits members experience. In reality, the value they create depends on the quality of the members in the group. For example, if a community has a bunch of “subtractors” or “dividers,” they may use your member directory to spam the rest of the group. On the contrary, getting six “multipliers” into a well-structured Zoom conversation can create amazing results.

Another reason not to overdo it on capabilities is that they increase the costs of maintaining your community. Once introduced, costly features can be hard to roll back. No one wants to fire a staff member or discontinue a popular event series. The best solution tends to be keeping costs low until you’re sure you’ve got a sticky community that drives real demand.

Pro tip: Ask your members to contribute

In the early days, when money is scarce, your community can punch above its weight by having members chip in to perform various functions. Don’t be afraid to ask members to act as forum moderators or event hosts. People are hungry to contribute in non-monetary ways. You may even want to create some kind of membership requirement around contribution so that members feel more invested in the success of the group.

Design your community to spark quality interactions

Interactions between members are the life-blood of your community. They’re the moments when value gets exchanged. Someone sends out a late-night Slack to the group admitting they feel stuck. Thoughtful responses that pour in within minutes from others who’ve been through it before. One member suggests a job at her company that would be a perfect fit and offers a referral. Sparking these engagements takes intentional work. If new members aren’t motivated or don’t understand how to create value, they are likely to disengage.

To motivate initial interactions, you’ll want to design your community to incentivize members with their first hit of value soon after they sign up. This value should arrive in a form that fulfills whatever need caused them to join in the first place. For example, I recently joined a writing group called Compound that has a couple of great magic moments:

- When you initially join the Slack group, the founders invite you to introduce yourself and share your publication. This leads to warm welcomes, new Twitter followers, and newsletter subscribers (leveraging the dopamine hits that social platforms are good at delivering).

- During onboarding, the founders explain that the core activity of the group is editing. You post your work and get a bunch of insightful comments. The first time you post something to the group and end up with a Google doc full of insightful comments, you can feel the value that the community has to offer.

When a community’s magic moment is effective, new members will crave more of this value. You want them to learn, early on, that the key to unlocking more value for themselves is to create it for others. As community architects, you have several levers at your disposal to incentivize this:

- Norms – the informal standards of behavior that the group agrees to and expects

- Policies – formal rules that govern the operations of the community

- Rituals – ongoing activities that define the type of interactions that take place among the group

- Rewards – Incentives put in place to motivate positive behaviors

Compound, for example, has a norm that each time you post a piece of work to be edited, you should, in turn, edit someone else’s work. They also have a policy of only accepting serious writers, so that they can be sure members are capable of delivering real value to one another.

When starting a new community, it’s helpful to focus your efforts around a single type of interaction where value can be given or received. It could be answering questions, providing feedback, or celebrating achievements. Whatever it is, the more you can reduce friction around this interaction, the more value members will gain.

The two levels of group cohesion

As members create value for one another, the group will start to bond at two different levels. The first involves the relationships between individual members, and the second is the affinity members feel with the group itself. Both of these are critical if you want your group to have a transformational impact.

Level One: Individual Relationships

When status hierarchies are transparent, it can be hard to build and maintain high-quality relationships. Humans often gravitate toward those of a similar or higher status, which naturally leads to the highest status individuals getting the bulk of the attention. Since these people get a lot of attention anyway, they will eventually grow tired of the community and leave.

To fix this problem, you’ll want to intentionally architect a community that gives people minimal credit for external status markers and forces them to build status within the environment of the community. For example, suppose a seasoned executive and a new college grad join the same running club. In that case, the two will have a much better chance of forming a relationship if minimal emphasis is placed on the professional status differential between them. By instead bestowing status based on something like number of runs attended, the club can create a separate status economy that members can partake in. Ideally, internal status should reward activities that align with the members’ individual goals and community needs.

Level Two: Group Affinity

Members’ relationships with the group itself must be thoughtfully cultivated through a set of unique cultural practices and shared experiences. Uniqueness is vital because you want your members to feel united by a shared history. If the experiences are common, your members can talk about them with anyone. This is one reason fraternities and sororities have long “pledging” processes full of strange and secretive activities. They want to force new members to bond with other members of their pledge class.

Hosting a thoughtful onboarding is one way to create a shared experience that instills new members with the right behaviors. Putting some effort into this upfront will make it much easier for the community to moderate itself as new members get assimilated.

It can also make sense to set up some type of minimum requirement around membership that aligns with the reasons members signed up in the first place. If it’s a writing community, have a publishing requirement. If it’s an exercise community, make your members share evidence of their workouts each month. As long as the requirement aligns with their goals, it will make the group more cohesive.

Recognizing and retaining key members

To retain members for the long term, they need to unlock new forms of value. One particularly useful incentive is community-based status. This can be delivered in small and large ways. For example, at SoulCycle, instructors greet regulars by name and celebrate their birthdays to make them feel like valued members of the community. College acapella or improv groups bestow status by handing out titles and responsibilities on tenured members.

Status tends to be sticky, and your members will do what they can to hold on to it. In turn, new members will naturally want to emulate these individuals to build their own status within the group.

Buzzing Communities author, Richard Millington suggests that as groups grow in size, it makes sense to create insider groups that are explicitly responsible for:

- Soliciting and communicating feedback from members

- Volunteering to manage specific areas of the community

- Weighing in on important changes to the community

These groups tend to be effective because they tie status and contribution together.

Pro Tip: Go above and beyond

From time to time, your members will experience real hardship. A spouse will fall ill. A house will burn down. The list is endless. When these calamities strike, your members may turn to your community for support. Far from an inconvenience, these moments should represent an opportunity for you to leverage your community’s full might to help distressed members get back on their feet. Not only will this practice create a great culture within your group, but it will help build lasting loyalty and trust.

Growing your ranks

If your community can create a transformative experience for members, their friends and acquaintances will naturally take notice and want to join. At this point, you will get to choose if you’re going to leverage this demand to grow or to become more exclusive.

Assuming your community charges dues, becoming bigger will give you more resources to invest in the type of capabilities that drive value. On the other hand, going the exclusivity route makes admission to your community scarce, and therefore more valuable to new and existing members. Thriving communities tend to trade off between these two strategies.

If you can’t generate enough demand by word of mouth alone, you may decide to experiment with some other growth channels. To ensure you don’t waste time screening people who aren’t a fit, be intentional with how you target your distribution efforts. If your community is for serious athletes, you might send messages on Instagram to people who post photos of themselves working out. If you are seeking high caliber executives, you might use Linkedin messages to find new members with the right titles.

Keep in mind the fundamental truth that people want what they cannot have. If you advertise your community all over the internet, you may generate awareness, but you will not create much demand. In reality, the type of interest you want can only be generated by having a lasting positive impact on your members’ lives.

A Time to Build

As a community builder, you have an opportunity to play a part in reknitting our frayed social fabric. Hopefully, this guide has inspired you to think bigger about what your community might be able to accomplish and provided you some suggestions to help you realize your ambition.

This, of course, is just scratching the surface. If you want to dive deeper here are a few books that are worth checking out:

- Buzzing Communities by Richard Millington

- The Art of Gathering by Priya Parker

- Get Together by Bailey Richardson, Kevin Huynh, and Kai Elmer Sotto

- The Art of Community by Charles Vogl

This post was significantly improved thanks to the great folks over at Compound Writing. I’d specifically like to thank: Alberto Arenaza, Ashley deWilde, Dan Hunt, Casey Rosengren, Joel Christiansen, Joshua Mitchell, Justin Mares, Kevin Lee, Lenny Rachitsky, Sarah duRivage-Jacobs for providing thoughtful feedback on early drafts of this post.

Header image by Mirko Grisendi