The T-Shaped Information Diet

Somewhere out there is an idea that could change your life...

This post was originally published in The Jungle Gym.

Somewhere out there is an idea that could change your life, like:

- The marketing experiment that could 10x your company’s growth trajectory

- The investing tip that could make you a centimillionaire

- The health habit that could add a decade to your lifespan

There’s just one problem; you haven’t encountered that life-changing idea. Not yet, at least.

The best way to discover it is by getting intentional about the inputs that make up your information diet.

In the words of Atomic Habits author James Clear:

I find that almost every thought I have is downstream from what I consume. If you have better inputs, you naturally get better outputs.

To get better inputs, you’ll need to subscribe to some high-quality information streams.

But not just any information stream will do.

Our attention spans are finite, which raises the opportunity cost for subscribing to any given source. The challenge is to weed out sub-optimal information streams to make room for those that consistently deliver valuable insight.

This essay will cover some principles you can use to cultivate a high-quality information diet to capture the benefit of more life-changing ideas.

The T-Shaped Information Diet

The T-shaped talent model suggests that the best way to grow your abilities is to build a shallow understanding across a breadth of domains and a depth of expertise in whichever domain is most relevant to your profession.

This same lens helps identify which topics to prioritize within your information diet.

To build the vertical bar of your T, you’ll want to subscribe to information streams that help you perform the important roles and responsibilities you’ve signed up for in your personal and professional life.

Here are a few of the key roles I play:

- Product Marketer

- Newsletter Publisher

- Husband

- Self-Maintainer

To be effective in those roles, I need to ensure my information sources contain insights that help me perform.

For example, in my role as a product marketer, I sell a workforce education platform to HR leaders. Accordingly, I tap into domain-specific information streams that bring me:

- Insight about marketing from influential writers like Rory Sutherland and Julian Shapiro.

- Perspective on education and employment from publications like Emsi as well as thinkers like Michael Horn.

- Understanding of the HR function from thought-leaders like Josh Bersin and communities like The Institute for Corporate Productivity.

By mapping out your personal and professional responsibilities, you should get a good idea about which topics the vertical bar of your information diet should include.

The real magic comes from selecting the sources for your horizontal bar.

These can come from a broad range of domains, including:

- Ancient Philosophy

- Politics

- Scientific Research

- Fiction

While these sources may seem less consistently relevant to key roles you play, they will help generate unique and creative approaches to the challenges encountered over the course of your work and life.

As a marketer, I have benefited by incorporating information sources that other marketers don’t, including:

- Eric Weinstein’s podcast covering the distributed idea suppression complex

- Joseph Henrich’s books about cultural learning as the key to human success

- Jordan Hall’s videos interpreting the paradigm shift that’s transforming how we make sense of reality

Your T-shaped information diet should fit the roles you play and the domains that interest you.

As you seek out information streams, it can be tempting to go overboard subscribing to new podcasts and newsletters. Remember: your attention is finite--overburdening yourself with information isn’t the answer.

Just as a good diet isn’t judged by the quantity of food you eat, a good information diet doesn’t depend on how much information you consume. Your best bet is to select a smaller number of high-quality information sources.

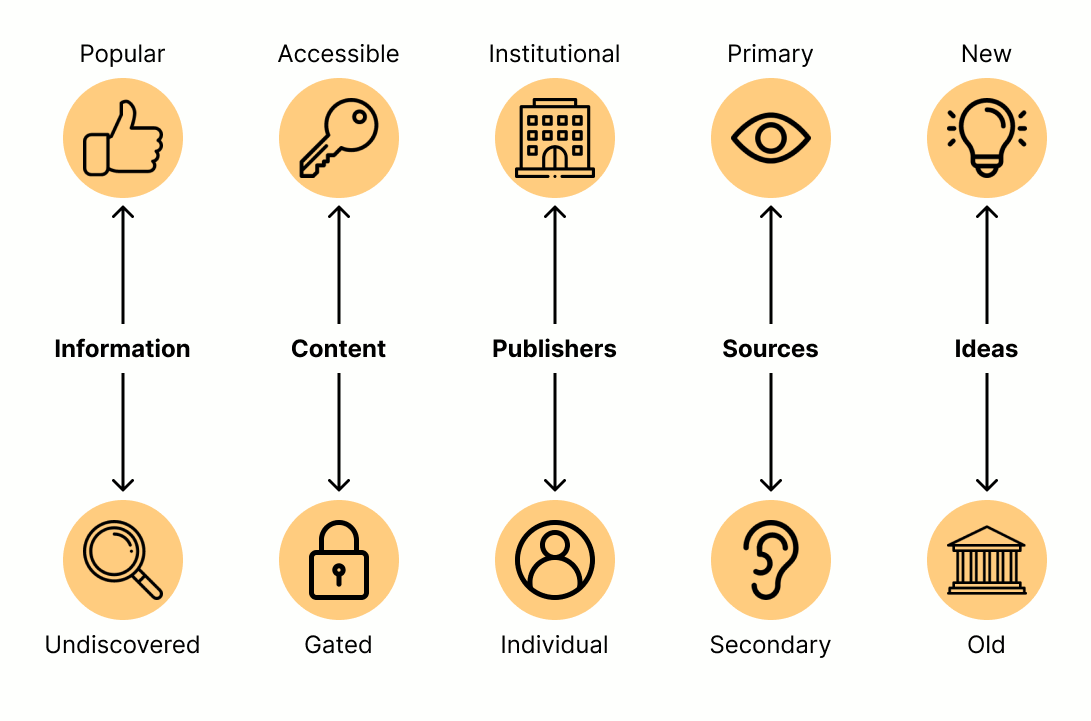

In the sections ahead, we’ll cover some principles that will help you evaluate potential sources of information to add to your diet, including:

- Popular vs. Undiscovered Information

- Open access vs. Gated Content

- Institutional vs. Individual Publishers

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- New vs. Old Ideas

Principles for Selecting High-Quality Sources

Let’s look at how each of these principles contributes to the construction of a healthy information diet.

Undiscovered vs. Popular Knowledge

Imagine, back in 2013, you discovered a convincing explanation of why Bitcoin will be a trillion-dollar asset. Had you traded on that belief before most of the world had heard of cryptocurrency (and cashed out in 2021), you would have been rewarded handsomely.

Therein lies the value of an undiscovered information source. Because few people are tapping into it, you can gain by acting on it first.

But undiscovered information isn’t the only way to get an edge. There’s also an advantage in knowing things that others know.

For example, if you and your manager have both read the same book, you can reference it when collaborating. If your whole company has read the book, you can mention it in an all-company meeting to convey an idea to everyone.

In this way, widely accessible information has a network effect where each person with access to an idea can provide benefit to others who are familiar with it.

To access both of these advantages, you’ll want to tap into undiscovered as well as popular information streams.

For example, let’s say you work in corporate strategy at a tech company. You might want to subscribe to an established newsletter like Stratechery to ensure you have the context you need when your boss mentions aggregation theory.

But that alone won’t leave you with much unique insight to contribute to the conversation. That’s why you might also want to subscribe to an up-and-coming strategy newsletter like Not Boring, Divinations, or The Generalist.

Ideally, you can combine the advantages of popular and undiscovered information by finding valuable ideas early and benefitting from them as they grow in popularity.

Accessible vs. Gated Sources

One way to ensure you’re getting the advantages of both popular and undiscovered information is by tapping into a mix of accessible and gated content.

It’s helpful to think about content accessibility as a spectrum.

The most accessible piece of content might be a link to a blog-post with no restrictions. As gates get added, accessibility decreases. A few common gates that reduce accessibility are:

- Financial gates for content that costs money (books, paid newsletters)

- Data gates for content that can only be accessed after you submit personal information, like an email address (corporate reports)

- Knowledge gates for information that requires a prior domain knowledge before it can be understood (whitepapers, scientific research)

- Relationship gates for information that requires a relationship with the author for access (communities, private data sets)

- Time gates for information that requires a serious investment of time to access (insights embedded in the middle of long videos or podcasts)

When evaluating a gated source of information, start with the accessible content. For example, to decide whether to pay for a newsletter, sample the author’s free writing. If you find it consistently insightful, it’s probably worth it to deepen your commitment.

Institutional vs. Individual Publishers

For the better part of the last century, institutions have controlled how we access information.

- News organizations selected which stories they printed in their papers

- Academic publishers determined which research to include in their journals

- Broadcasters decided what segments got shared during their news programs

The benefit of institutionally-mediated information is that it gets filtered by gatekeepers who ensure the content meets the standards of their institution.

The problem with this process is that it can distort the intended message.

Picture a real-life game of telephone. An insight may originate from a researcher, but by the time it’s passed through the inboxes of an academic publication, a journalist, and a newspaper editor, the meaning of the message may be significantly altered.

Gatekeepers can also distort messages, frame them in misleading ways, or filter them out entirely.

An alternative to institutional information is to subscribe directly to individual thinkers. While you miss out on the institutional certification, you get access to insights that are far less susceptible to censorship.

Unfortunately, identifying high-signal thinkers is hard.

While follower counts on platforms like Twitter can be useful, these metrics can be gamed.

Ask friends and co-workers who they follow, then perform your own diligence by evaluating a thinker’s ability to:

- Find and curate quality content

- Contextualize others’ ideas with their own insight

- Create original ideas

For example, Cedric Chin is one of the most insightful people writing about careers. Each week he publishes a newsletter with an original essay and curates a bunch of links. If he recommends something, it’s usually worth reading. Plus, his editorial provides an extra layer of context that usually improves my reading experience.

By subscribing to a mix of individual thinkers and institutional publications, you receive a holistic sense of the conversation. Individuals give you early access to unfiltered insight while institutions can help you identify which ideas are making their way into the mainstream.

Primary vs. Secondary Sources

To build an accurate model of the world, it’s useful to pepper your diet with primary and secondary sources.

- Primary sources of information illuminate base reality

- Secondary sources add a layer of interpretation

Given the amount of misinformation in our environment, you need ways to study reality for yourself and check your interpretations against trustworthy sensemakers.

For example, when I wanted to wrap my head around the insurrection at the capitol, I started out by forming my own opinion using primary sources of authentic videos on YouTube. I also wanted to get a sense of how people across the ideological spectrum were interpreting it. So I turned to:

- The Daily from The New York Times for an establishment left perspective

- The Dark Horse Podcast from Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying for a left-of-center perspective

- The Remnant from Jonah Goldberg for a right-of-center perspective

- The Fifth Column from Kmele Foster, Michael Moynihan, and Matt Welch’s for a libertarian perspective

- The Roundtable from The Claremont Institute for a populist right perspective

You’ll notice I’m not looking for impartial secondary sources. Instead, I am collecting a spectrum of convincing ideological perspectives that force me to grapple with different interpretations.

New vs. Old Ideas

It’s easy to fall into the trap of getting obsessed with new ideas.

Though novelty implies that an idea might offer a competitive edge, it should make you wary. New ideas have not been battle-tested by ideological opponents or withstood the test of prolonged scrutiny, making them risky to act upon.

To balance the new information that will naturally flow to you, make sure you’re seeking out old ideas as well. These ideas are often contained in books that have managed to avoid getting buried by the noise of history. Perhaps the best explanation of the value of books comes from a relatively old (in the context of the internet) speech from William Deresiewicz:

Most books are old. This is not a disadvantage: this is precisely what makes them valuable. They stand against the conventional wisdom of today simply because they’re not from today. Even if they merely reflect the conventional wisdom of their own day, they say something different from what you hear all the time.

But the great books, the ones you find on a syllabus, the ones people have continued to read, don’t reflect the conventional wisdom of their day. They say things that have the permanent power to disrupt our habits of thought. They were revolutionary in their own time, and they are still revolutionary today.

That said, don’t go overboard. It can be easy to over-index old ideas and lose touch with the zeitgeist of the moment. While being constantly plugged into the current conversation has drawbacks, it’s also hard to get by as a modern knowledge worker without staying in touch with what’s going on in the present.

Balance is the key. Old ideas often provide the frames to allow you to process new ones more clearly. Conversely, new ideas test old ones to see if they still have explanatory value. You need a mix of both.

Putting it into practice

You may be feeling a bit overwhelmed at this point, wondering how you’re going to build yourself a healthy diet that accounts for all of these factors.

Remember, information consumption is rarely the end goal. Instead, it’s to surface high-signal insights that help you live a longer, happier, and richer life.

To put these ideas into practice:

- Map out the essential roles and responsibilities in your personal and professional life. This will give you a sense of contexts in which you use information.

- Make a list of the information sources (blogs, podcasts, newsletters, literary authors, communities, Youtube Channels, etc.) that you depend on for useful insight and map them to the roles and responsibilities they help you perform.

- If you feel inspired, rank each one by insight quality or any other dimension discussed in this post.

- Unsubscribe from any sources that aren’t at least above a 7 or 8

- Start seeking out new information sources in areas where your diet is lacking. Often asking for recommendations from friends or on Twitter can be a good place to start.

The best strategy with eating is to be intentional about the food you put in your body.

The same holds for information.

Be thoughtful about the information you consume, since the information you consume will soon become your thoughts.