Work and Let Work

Three models for managing political conflict in the workplace

This post was originally published in The Jungle Gym.

If you’ve any spent time on Twitter recently, you likely encountered this manifesto from Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong discouraging political advocacy at his company.

The resulting debate both strengthened Armstong’s case for the toxicity of politics and managed to embroil him in the type of controversy he hoped to rid from his company.

Whatever your opinion about the memo, it’s hard to deny that we humans aren’t very good at restraining our political polarization. This is particularly true in 2020, when our party affiliations have become so intertwined with our identities.

How can companies prevent political conflict from undermining company cohesion? Here are three models to consider for anyone attempting to build an organizational culture:

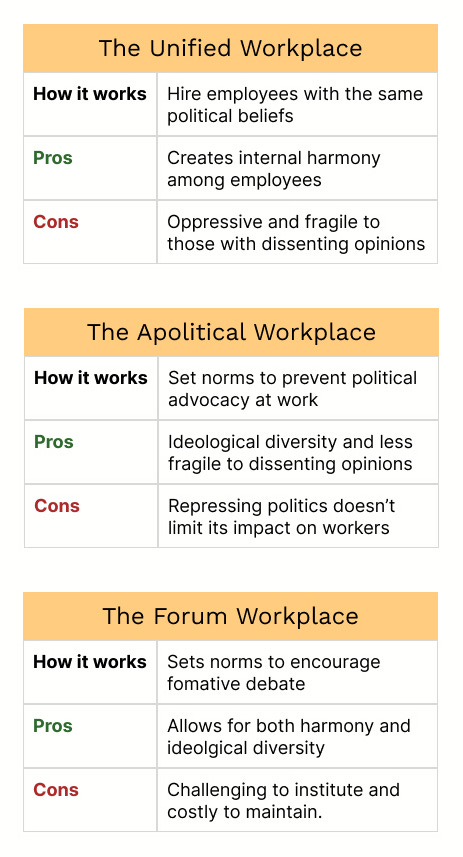

Model #1: The Unified Workplace

Companies using this model hire employees who share similar beliefs about most contentious topics. This allows workers to share their views on issues like abortion, gun rights, and immigration without worrying about creating conflict with co-workers.

To build and maintain this model, companies must:

- Pick a popular party affiliation

- Publicly express values that dissuade employees with incompatible beliefs from applying

- Screen out candidates with misaligned views during the hiring process (Note: some states protect job seekers from this type of political discrimination)

This strategy can work for both left and right-leaning companies. It’s safe to say that Patagonia and Ben & Jerry’s don’t spend much energy mediating the opinions of Trump-voting employees. Likewise, Hobby Lobby and Chik-fil-A probably get very few job applications from AOC supporters.

With this type of model, it’s less important whether an employee shares the dominant position on an issue than whether they stand in opposition. For example, in a left-leaning company, an employee who’s ambivalent about abortion doesn’t threaten the peace. Meanwhile, an avid pro-life employee can create a lot of controversy.

When this approach works, it creates harmony on several levels. The company stays compatible with its customers. Managers don’t need to mediate heated political debates. Individual employees can go to work without repressing their views on topics they care about.

The disadvantage of this model is that it’s fragile. Take Google. While the company may not explicitly follow this model, its employee base certainly leans progressive. This made James Damore’s 2017 memo accusing Google of being an ideological echo chamber all the more explosive.

This model can also be oppressive to workers with divergent political views that slip through the hiring filter. It’s hard enough to navigate typical workplace politics without learning and performing your boss’ political beliefs. While workers always have the right to part ways with their employers, this option is significantly riskier for low-wage workers living paycheck to paycheck.

In response to these drawbacks, companies like Coinbase have pushed to remove workplace politics altogether.

Model #2: The Apolitical Workplace

Rather than filtering employees based on their views, the apolitical workplace restricts political advocacy altogether.

To work, this model requires enforcement at the top and bottom of the organization. The CEO must remain neutral and not influence employees toward his or her favorite political party. However, the CEO can’t monitor every Zoom meeting and Slack conversation. Employees must believe enough in neutrality to avoid the temptation of impromptu political conflict.

Apolitical companies have the potential to sustain much more ideological diversity than unified ones. This allows them to craft messages and build products that appeal to a much broader market.

They are also less fragile to flare-ups of political conflict since employees have implicitly agreed to restrain their politics. Returning to the Damore memo, it would have been much easier for an organization like Coinbase to discipline the author since the company would have had norms against that type of expression.

The problem with this model is that it assumes repressing politics can make it go away. This simply isn’t the case. When workers are forced to grapple with America’s health care or criminal justice systems, you can be sure they will bring these experiences into work. If employees feel pressured to withhold these feelings from coworkers, they are depriving their manager and teammates of the type of critical information needed to maintain a functioning team.

So is there some kind of happy medium?

Model #3: The Forum Workplace

The Forum Workplace attempts to foster both ideological diversity and political engagement, without unleashing conflict. To pull this off, companies need to distinguish between two types of debate:

- Formative debate – where the purpose is to express ideas that change minds

- Performative debate – where the goal is tribal signaling and public shaming

To create a culture that fosters formative debate requires enforcing norms that sit above the political beliefs or emotional state of any single employee. Some examples of useful norms include:

- Handling political disagreements through direct exchanges vs. public forums, like Slack

- Avoiding divisive labels or impugning others’ motives

- Attempting to steelman arguments before attacking them

- Creating a culture that celebrates “belief updating”

When executed thoughtfully, this model should offer the advantages of political diversity and free expression without the drawbacks of the unified or apolitical workplaces.

So why don’t all companies use this model? Because it’s not a competency most businesses are willing to prioritize. Companies only have so many resources to invest in creating culture. Is promoting formative debate more valuable than creating a culture of customer obsession or product excellence? Probably not.

There’s also no guarantee investments here will produce a return. Even institutions like universities, that are designed to foster open inquiry, have trouble building fostering formative debate.

Work and Let Work

Each of these models has its benefits and drawbacks:

Each of them should be tried, along with plenty of other experiments.

As someone who enjoys formative political debate and having his mind changed, I can’t imagine enjoying working at Coinbase. But I also don’t think I’d like working at a company that encourages unfiltered political discourse either. Luckily, there are lots of companies to choose from, and they aren’t all trying the same thing.

Before the rise of social media, one thing that limited political conflict in our country was the ability of groups to start experimental communities. This allowed cities ranging from Berkeley, California (one of the most progressive cities in America) to Mesa, Arizona (one of the most conservative) to try building their own utopias. If these people had to share the same city, they would all be miserable.

The same holds when it comes to companies. If Patagonia or Chik-Fil-A employees had to work together, they would all be worse off.

As long as companies follow the laws, don’t discriminate, are inclusive of those who share their values, and allow people to exit if they aren’t happy, we should let these experiments run.

What’s important is that leaders are intentional about the cultures they are building and proactively communicate their values to potential hires.

Coinbase’s experiment is as useful as any other. If it turns out no one wants to work there, we will all have learned a valuable lesson. If it becomes a hotbed for productive innovation, we can figure out how to replicate and improve on its model.

Work and let work.