Career Transition Risk and the Ladder of Legitimacy

A playbook for overcoming the objections of your future hiring manager.

By their nature, career transitions tend to involve a lot of self-centered thinking.

What do I want to do with my life?

What will make me feel fulfilled?

Questions like these are important, but, they only solve part of the problem. On the other side of any career transition there exist one or more people who must agree to take on the risk of a junior hire. To land a dream job, you’ll need to understand how these stakeholders think about risk so you can plan the steps of your transition accordingly.

When coaching Tradecraft members through career transitions, we try to get them to think like their future employers. For companies, hiring is a pain. Valuable team members must devote hours of time to interviews and hiring committees, instead of revenue-generating activities. Once a hire is made, more time must be spent training and orienting the newcomer. If the hire doesn’t work out, the company will need to pay severance and deal with ramifications of the hire’s poor performance. In total it represents a good deal of risk for any employer.

While the whole company shares in this risk, the hiring manager often bears the largest share. A manager’s performance is judged on the output of his team and a bad hire can significantly drag down that output. Since a poorly performing team can limit the manager’s career growth, hiring managers tend to be naturally risk averse.

Since it’s hard to know whether a team member will work out, most hiring managers cover their asses by hiring candidates with obvious signals of legitimacy. That way, if a hire doesn’t work out, the hiring manager can say, “well, who’d have thought that someone who worked at Google would have been such a bad fit?” In the vein of the oft-cited saying that “no one ever got fired for buying IBM,” no one ever got fired for hiring from Google.

New hires can represent several different types of risk, including:

- Functional risk– Can the candidate accomplish the objectives of this role?

- Stage risk — Does the candidate have experience operating in a work environment like this one?

- Culture risk — Will the candidate’s values, attitudes, and habits mix well with the other people on this team?

- Customer risk — Does the candidate have experience solving problems or creating solutions for our customer?

- Problem risk — Has the candidate created solutions to solve this type of problem before?

- Solution risk — How comfortable is the candidate with the process of building and selling this type of solution?

The way most hiring managers see it, the least risky employee is one who has done the exact same job before, in as similar of a context as possible (note that I don’t believe this is the right philosophy).

To understand how much career transition risk you’re taking on, ask yourself how much hiring risk your future manager will need to bare. The more elements of your job you try to change from one opportunity to the next, the more that risk will grow.

What can you do about it?

You have two levers at your disposal to deal with transition risk:

- Offer more

- Ask for less

To offer more you’ll either need to expand the abilities you can share with your employer, or the time you can devote to work. In my experience, most transitioners understand the value of this lever. They believe that by spending enough time building skills or demonstrating their dedication, an employer will give them a shot. While, of course, this is an essential part of any transition I think it’s lever #2 that’s underrated.

Ultimately, the catch 22 of any career transition is that hiring managers want to see that you have experience doing the job, which you can only get through a job offer. So, how can you convince employers to give you a shot, in the first place?

By asking for less.

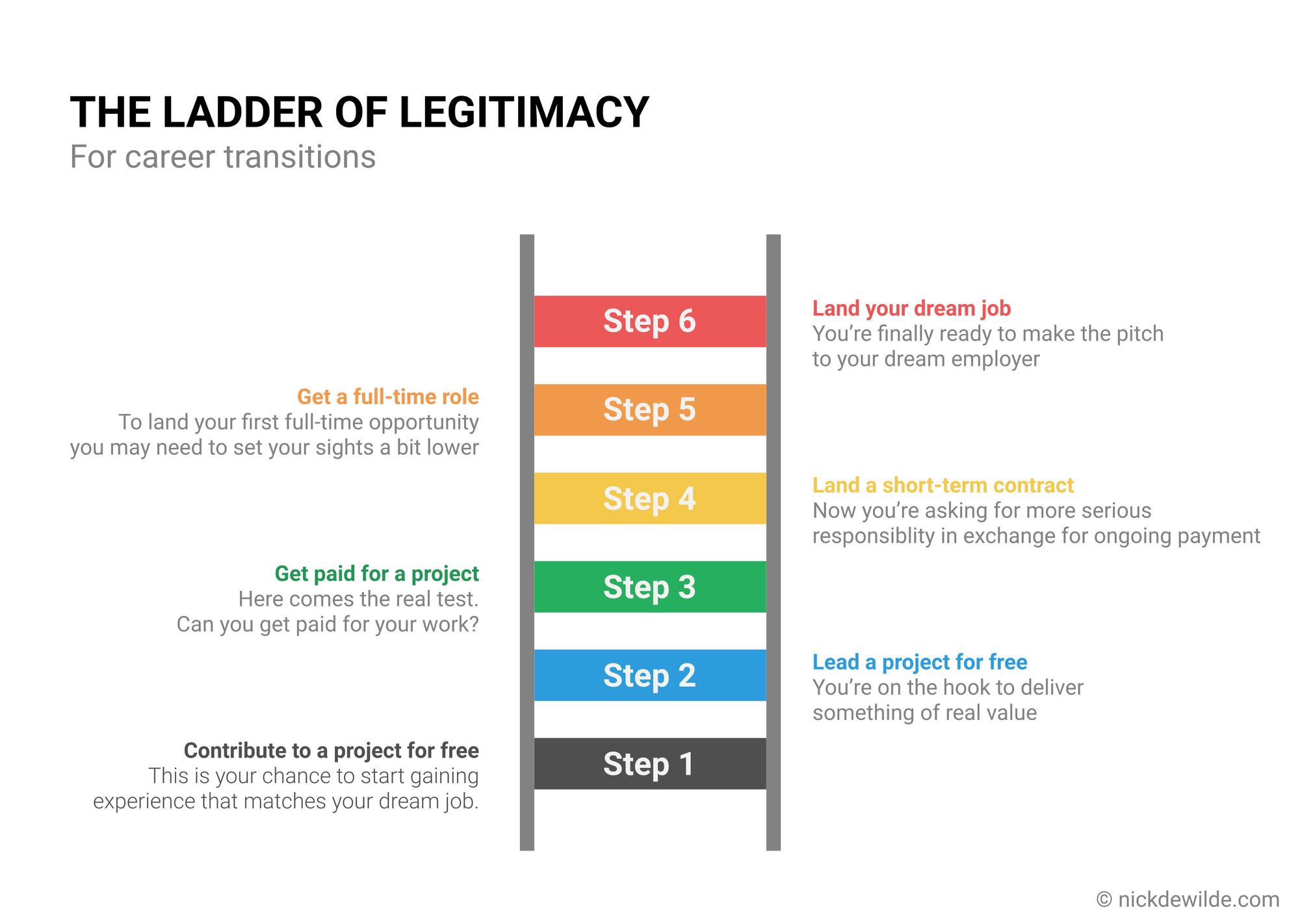

In practice, this means making a smaller ask from your prospective employer. This might mean you initially lower your hourly rate or even offer to do work for free. Rather than trying to get for a full-time job right away, you give employers the chance to try you out before making a long-term commitment. As you gain more experience you can then ask for a bit more. I think of this as climbing a ladder of legitimacy. To illustrate how it works, let’s look at a case study.

Michelle is an architect who dreams of landing a product design role at Slack. In her current role, she represents almost every type of risk to her future employer. She has no experience with Slack’s customer, problem, or solution. Furthermore, her architecture firm is small, has grown slowly, and has a very different culture from Slack. While Michelle does have a functional skill set that crosses over with digital product design, she hasn’t used it to create software products. Given all this, it’s unlikely Michelle will be getting her first offer from Slack. But that doesn’t mean she can’t get there eventually.

Assuming Michelle has the intellect and motivation to build the skills she needs, let’s look at how she might climb the ladder of legitimacy to mitigate some risk for her future employer.

Step #1: Contribute to a project for free

This allows Michelle to get her hands dirty and start gaining experience. She’s mitigating some hiring risk by involving more experienced people and working for free. While it may seem like a small ask to contribute to a project for free, she’s asking both the other contributors and the client to entrust her with sensitive information and time.

Step #2: Lead a project for free

She’ll now need to demonstrate that she can make the rest of her team look good by delivering a quality work product in a timely manner. In selecting which projects to work on, she may want to consider projects at companies that share a similar problem, customer, or solution to Slack.

Step #3: Get paid for project work

Michelle isn’t yet asking for a short term role. Just a single project. The difference this time is that she’s looking to get paid in return. This might be the hardest step of Michelle’s ladder. If she’s unable to find the right opportunity Michelle can:

- Offer a money-back guarantee

- Ask for a lower rate

- Downscope the size of the project

- Bring other members on the team with more legitimacy

Step #4: Land a short-term contract

Michelle’s now looking more serious responsibility in return for ongoing payment. While the contract is limited which means the client doesn’t need to worry about paying severance if things don’t work, it’s certainly not without some risk. If Michelle’s having trouble getting traction at this step, she can always lower her hourly rate. Again, this will be a great opportunity to look for a company with some similarities to Slack.

Step #5: Get a full-time role

While this may seem like the top rung of the ladder, Michelle may still be a ways off from her ideal role at Slack. First, she may need to take a chance on a lesser-known company or a larger employer that’s lost its luster.

Step #6: Land your dream job

Assuming Michelle has kicked ass at her last company, and gained some relevant experience, she’s now in a much better position to go for that dream job. Keep in mind, if the company is really hot (let’s say Slack in 2016, or a company like Opendoor today) she may be looking at a few more rungs between #5 and #6.

While this may seem like a lot of added steps, climbing one rung at a time will ultimately get you to your goal faster. Instead of spending your job search waiting for emails to be returned while watching your bank account dwindle away, you can start gaining experience and income much sooner.

You can also speed these steps up. For example, no one says that your first full-time role needs to last two years. One year, or even six months, may allow you to level up to a more desirable role. You can also speed things along by combining steps. By taking two part-time roles or more than one project, you can build momentum and confidence that will help propel you to your next opportunity.

Career transitions can be a humbling experience. If you’re used to being sought-after by employers, their new-found apathy will likely feel demoralizing. Instead of setting yourself up for the inevitable rejection that comes from changing every part of your job at once, try making a series of smaller changes. Ultimately you’ll be able to regain your former career capital by climbing the ladder one step at a time.